Get clarity on a problem to be solved – either by yourself or as a team – by exploring it, reframing it and articulating it in a more insightful way using this simple visual pattern.

Ambiguity and confusion? You probably don’t have a proper problem statement

Have you ever had those times where you’re lying awake at night, with your mind gnawing on a problem, and you just can’t seem to think it through properly? You toss and turn, and as much as you want to turn your brain off, you can’t!

Or, you might have a project at work where you (and probably others too) can’t really say why you’re doing it. The project might have a goal, but still there’s no clear purpose. Sometimes people might even say smart things like “We need to know what problem this project is solving” (very true!) but still, nobody can actually articulate what the problem is.

Or you might even have a problem statement – or inherited a problem statement from somebody else – but it still just sounds like a goal.

A proper problem statement – and I can’t believe I have to say this – should contain a problem. Something that is in the way of someone (or a business, or a system) achieving a goal. Yes, the statement itself can contain the goal, and yes it should say something about who has the problem, and no it should definitely not already contain the solution. Here’s a good guide that has always helped me:

[Persona / Customer type] wants to [Goal] but [Problem]. This is unacceptable because [Impact].

Note how adding the impact of the problem helps to say why we need to solve this particular problem, and maybe why we need to solve it now.

Is it hard to come up with such a succinct, insightful problem statement? Usually, yes. Do you come up with it just by getting a group of people to talk? Probably not. Problem framing by definition is all about describing a problem from a specific point of view, and we all know how likely it is that everyone is going to have a different point of view!

That’s why it makes so much more sense to visually map out the problem space, to get clarity and alignment first, before being able to distill it all into a problem statement. And that’s where the Problem Pyramid comes in!

What is the Problem Pyramid?

The Problem Pyramid is a visual pattern you can draw to help you explore and clarify a particular problem space, especially if that problem space is complex, ambiguous or misunderstood. You use it give more structure and meaning to any conversation about the problem space, so that you have a better chance of distilling a more insightful problem statement.

When do I use the Problem Pyramid?

You can apply this to all sorts of problems and in different situations, such as:

- You have a problem, you’ve tried one or more solutions, but you can’t crack it yet

- A team is struggling with the scope and purpose of a project, and needs a shared clear understanding of its intent

- You’ve been given a problem statement, but it’s not helping to point the way to a solution

- You’re ‘selling a solution’ about a particular problem to management, and you want to check your thinking by asking yourself the hard questions up front

What is the Problem Pyramid made up of?

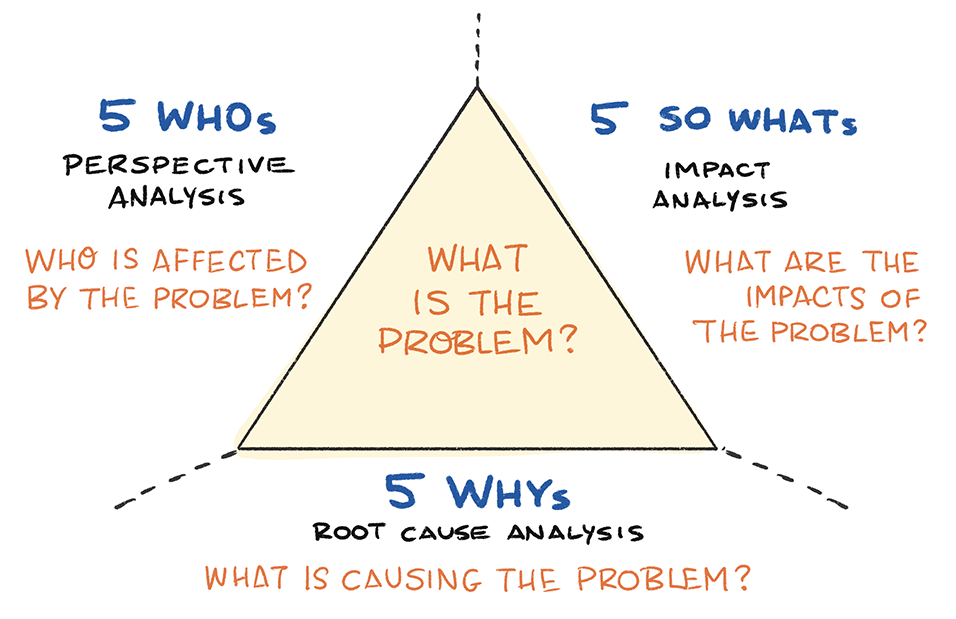

Take a look at the sketch below:

In the triangle you write whatever you think is the problem you need to solve (this is the existing problem statement). The triangle (or pyramid) has 3 sides, which symbolise 3 different ways to explore that problem:

- 5 Whys – root cause analysis

- 5 Whos – perspective analysis

- 5 So whats – impact analysis

How do you do the Problem Pyramid?

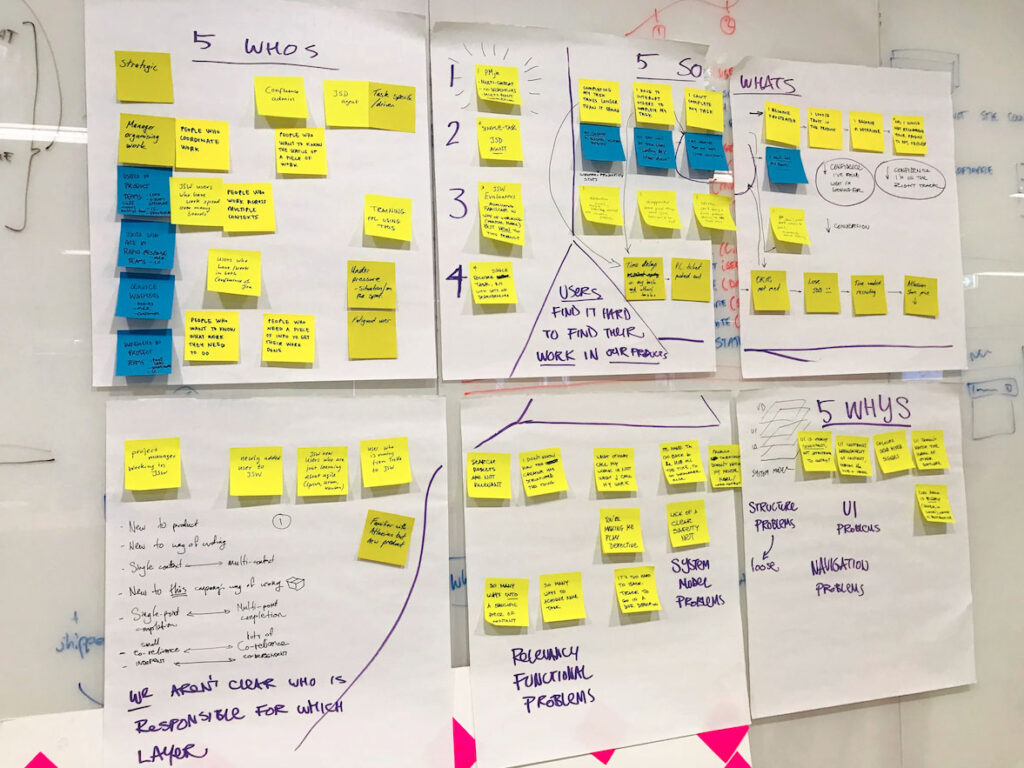

You can draw this Problem Pyramid on a whiteboard, paper, even in an online collaboration space (like Miro or Mural). You can do it with your team as a session on its own, or as part of an existing meeting.

Let’s take a look at how you and your team can tackle a problem by visually exploring each of these ‘sides’ together. Be sure to share some markers and sticky notes around for different people to add what they want to, at different points throughout this activity.

Start by drawing a large triangle in the centre of a whiteboard, and write what you think is the problem you’re trying to solve so far inside the triangle. This may well change… but you have to start somewhere!

5 Whys

Problems are usually tackled more effectively when they’re addressed at the source, rather than tackling just a symptom of the problem. The ‘5 Whys’ activity is well known in the design and product innovation domains, and helps us do root cause analysis. For more information about 5 Whys, see the Gamestorming 5 Whys activity or IDEO.org’s 5 Whys activity.

Ask everyone why the problem written in the large triangle is happening (or what is causing the problem), get them to write their responses on sticky notes, and stick them in the area below the large triangle. For example: if the problem is “We didn’t reach our quarterly target of selling 15 thousand shinklebots“, ask them “Why didn’t we sell 15 thousand shinklebots?”

There’ll probably be several different answers to this question that you can read on the sticky notes that people wrote, and you may need to group any duplicates. Now, take each response, and ask why again. For example, if one of the responses was “The factory couldn’t make the shinklebots fast enough“, ask “Why isn’t the factory making shinklebots fast enough?”, and so on. The ‘5’ in the ‘5 Whys’ is to get you and your team to really push your thinking beyond the default top-of-mind cause. The deeper you dig, the better insights you’ll get.

Before long, you’ll unearth some juicy root causes to the original problem that as a team you’ll want to focus on more than others. It’s tempting to now race off and solve one of those causes, but hold up! We have to explore the other two sides first…

5 Whos

Next, ask everyone who is affected by this problem, and get them to write on sticky notes (one per sticky note) who they think is most involved, and group as necessary. Depending on the nature of the problem, it’ll be a mix of particular types of customers, or types of staff members, or partners…maybe even you and your team.

If the team come up with more than 5 (there usually are more than 5), ask them: who is most affected by or involved in this problem?

Why do we do this? Because it’s important to get everyone out of their own mental bubble, and thinking of others. This isn’t a blame game at all; it’s about seeing who’s who in the whole system of the problem space. Identifying different kind of people affected by the problem then leads to helping to see and describe the problem through each of their perspectives, which is what re-framing is all about.

5 So whats

Thirdly, it’s good to do some impact analysis. Looking at the causes of the problem and types people who are most involved in the problem you have generated so far, ask “So what?” I don’t mean “So what?” in a glib, negative way, I mean: “What happens next for the people we identified? What’s the impact of that problem on each of them?”. Whatever the answer to that question is, ask “So what?” again, and so on.

For example: if the problem is “We didn’t reach our quarterly target of selling 15 thousand shinklebots“, asking “So what?” generates answers like:

- Quarterly revenue will be less than expected (business impact)

- We’ll need to work out why (action to take)

- There are too many shinklebots taking up space in the warehouse (business impact)

…and asking “So what?” again generates answers like:

- We don’t get the capital needed to open the new branch yet (business impact)

- We’ll need to temporarily divert some resources to do customer research (action to take)

- We need to find more warehouse space for the incoming products (business impact)

You can visually capture these in the same way as the other two ‘sides’ of the problem area, using a mix of writing, sticky notes and simple drawing on a whiteboard. You might like to ask “So what?” for each type of person you have isolated, too. Doing this impact analysis helps you and your team get a keener sense of urgency about the problem, as well as a sense of the impact if you delay action, or don’t do anything at all.

Step back and see the story

Now’s a great time to step back and get a sense of the whole problem space you and your team have generated. You now have a ‘map’ of the problem. It’s bound to contain some areas that are more tightly defined than other areas, as well as areas that may be completely new and insightful for you and others in the team.

You can use this ‘map’ to join up some elements that stick out as being more important. For example, there might be a specific customer type affected more than others, and the impact on them leads to more negative impacts on others. Or there might be an underlying cause that the team needs to focus on and fix, which will alleviate most of the impact for most of the people affected.

This is how the Problem Pyramid has visual storytelling power, as well as analytical power!

Try it yourself

As with all of the visual patterns I share, do let me know if you try it out, and what worked well, and what didn’t work so well. I hope this Problem Pyramid helps you see your problems better, so that you can solve them better!