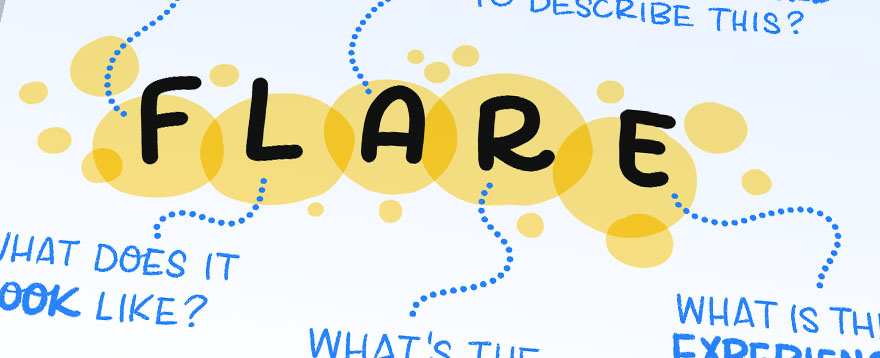

If you want to find ways to draw topics more creatively, or you feel like you’re in a bit of a rut drawing things the same way all the time, then the FLARE prompts are for you. How do you draw a person? Or a building? Or a tree? There are lots of ways to […]

Presto Sketching Blog

Volume 2 of Journey Mapping Icons out now!

I’ve just released a second volume of journey mapping sketched icons, containing 120 more icons. All images are in 300dpi PNG format, with transparent backgrounds, available for you to use in any way you like. You’ll find some additions to existing categories found in the Volume 1 set of icons, including expressions, people, devices, technology, […]

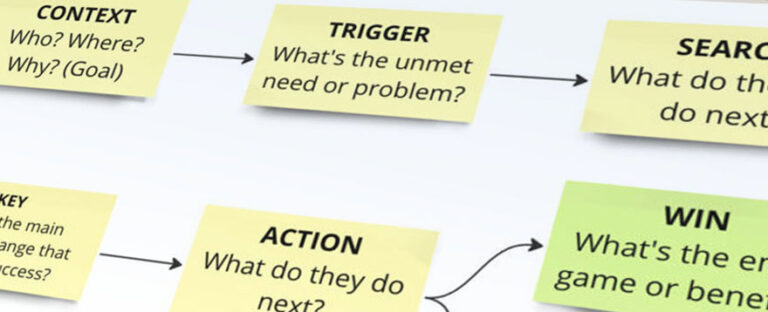

How to construct a great story

As I’ve written about before (and in my Presto Sketching book!), storyboards give you great bang for buck when you want clarity and direction in any project, especially for product and service design. Here’s how to construct the most essential ingredient: the story itself. Storyboards can guide you and your team from problem to solution […]

Why your project needs storyboarding

There’s that fantastic time in any product or service design project where an idea is just starting to take shape, and spread its wings. Will it be The Next Big Thing? Will it be able to stand up to the barrage of oncoming questions, like: will it resonate with your target audience? How will it […]

Here’s how AI visualises your company’s vision

UPDATE: I originally wrote this post in August 2022. AI-generated images have obviously come a long way since then. Please read this post with this in mind… I had a play with MidJourney to find out if it would steal my job as a visual practitioner or not, and the results were – well – […]

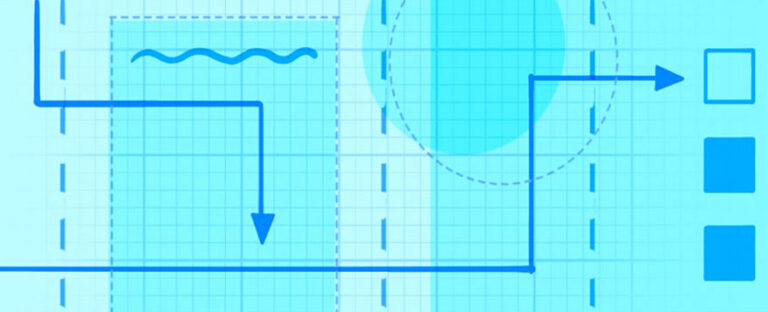

5 principles of great layout for your visuals

Your visual communication pieces can land with your audience or miss them entirely, depending on what layout you choose. This post shows you the principles behind why some layouts work better than others. Layout: your secret sauce for communication success One of the questions I get asked a lot in the training sessions I do […]

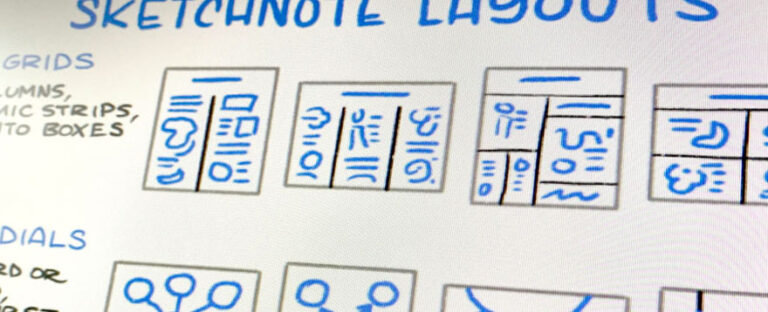

A guide to sketchnote layouts

Here’s a set of sketchnote layouts to try, plus some tips about which layouts to use for which particular purpose. Lead them down the garden path One of the questions I get asked a lot in the training sessions I do about sketchnoting (or visual note-taking) is: how do I organise content on the page? The […]